October is Selective Mutism Awareness Month

First of all, if you’re new to my site, or you’re just learning about this condition for the first time, welcome! I’m a software developer with a variety of interests, who fights a number of personal battles every day. One of these battles that, well, I don’t fight every day but I do fight on a regular basis, is an anxiety disorder called selective mutism. My anxiety manifests in several ways, but SM is the single most noticeable and predominant since I stopped experiencing panic attacks a few years ago.

Selective mutism is an anxiety disorder characterized by a consistent failure to speak in either specific situations or to specific people, in an individual who is otherwise physically able to speak (and can often be quite chatty in safe spaces such as home!). It affects people of all ages, but more children are diagnosed than adults as the childhood onset is better-researched and more widely understood. The Wikipedia article on selective mutism used to be incredibly barebones but it seems to be much more comprehensive now.

Although (and perhaps because) selective mutism is more commonly understood and treated in children, my article will not be focusing on children; instead, the focus of this article is on adults and teens with selective mutism. One big reason for this is that I never had selective mutism as a child; I grew up quiet and introverted, but not silent. I’m 26 years old now, and I’ve lived with selective mutism full-time for 9 years and 11 months, accurate to the day of the month. Thus, I believe that my experiences and tips will be more relevant to grown-ups than to parents of selectively mute children. (If you’re one such parent, I strongly encourage you to see a pediatrician and/or a speech pathologist.)

Table of contents

- How it all started

- What selective mutism feels like

- How I adjusted and made progress

- Diagnosis

- How you can help someone with selective mutism

- Emergency Chat and other AAC apps

- Selective mutism and autism spectrum disorder

- Selective mutism and speech disorders

- Awareness, acceptance and advocacy

How it all started

The first time I lost my ability to speak as a result of an anxiety attack was when I went to see High School Musical 3 (still one of my favorite movies of all time, as a non-moviegoer) with a friend I was very close with online. I was 16, coincidentally in my senior year of high school myself. I won’t say what exactly made me anxious, but it was unexpected and threw both me and my friend off-guard — only, she handled it much better than I did.

The movie was great, but the outcome of that outing, not so much, suffice to say. But compared to most teens and adults with SM, I’m actually incredibly fortunate because that has been the only time I felt like my loss of speech and poor handling of the situation had bitter consequences.

And here’s why I think that is: that evening, I had no alternative means of communication. This was three weeks before I owned my first smartphone. I had no paper to write on, and I did attempt to text my friend, but this being my first time experiencing it and hence stabbing in the dark not knowing how to handle it, sent my messages the usual way instead of showing them on-screen to her after typing them out, and I was unable to communicate to her to check her texts. (Presumably she eventually did but the outing was long over by then.) This catastrophic failure to communicate combined with my incredibly flustered demeanor at our first meetup had far-reaching implications for our friendship and other aspects of my life going forward.

And so SM continued to affect me profoundly through my college years. In my two and a half years (five semesters) of my diploma, only a dozen or so of my coursemates ever heard my voice, two heard me speak more than one sentence, and faculty were the only ones I succeeded at holding conversations with and presenting to. No one else in college heard my voice for two and a half years. That’s what untreated selective mutism looks like. I’m not a fringe case. That’s not even the scary part — the scary part is that this also happens to children, not just teens and adults. Fortunately, though, it’s much more commonly diagnosed, and successful intervention much more likely, in children.

In addition to being almost completely silent, I also had panic attacks, tons of them. (These were rarely influenced by, and did not influence, my silence.) Oh and I was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder in my second year, at the age of 18. I’ll discuss the relationship between selective mutism and autism in a later section.

What selective mutism feels like

Selective mutism, at its core, is an anxiety disorder. My typical experience is having the words to say, but being physically unable to vocalize them. My vocal cords tighten up and simply refuse to work even though they can and do work when I’m at home and in very specific safe situations or with specific people. My anxiety effectively disables my vocal cords, and any attempt I make to stimulate them rapidly increases my stress and anxiety. Doing so once caused me to collapse in front of a group of people who were repeatedly trying to make me speak, convinced I eventually would with persuasion (needless to say, they were proven wrong).

The only problem with the word “selective” is that although it’s understood in medical parlance to mean “only in specific situations or with specific stimuli”, to the average person it implies choice. And to a casual observer or even a conversation partner, it can come across as shyness, rudeness or defiance. Selective mutism is not a choice to withhold one’s speech, and it is neither rude nor disrespectful. At least, we don’t mean it that way.

Ever heard of the expression “paralyzed with fear”? That’s pretty much what SM is like for me — my vocal cords are paralyzed. You don’t run for your life not because you choose to stand your ground, but because you can’t. Likewise, when I become non-verbal, it’s not because I don’t want to speak, but because I can’t.

It’s also important to know that being unable to speak to you doesn’t mean that I don’t trust you or I’m afraid of you or I dislike you. In fact, I’d say that my selective mutism is primarily situation- and environment-based rather than person-based. That means that I’m more likely to be unable to speak in certain situations and environments than to certain individuals. It also means that selective mutism can prevent me from speaking to people I’m otherwise comfortable and even chummy with. Even my closest friends only get to hear my voice less than once a year. Of course, different people with SM may present differently, and this needs to be discovered in one’s own time.

When I first enter a social situation with my speech intact, if I lose my speech as a result of anxiety, I rarely get it back until I’m home. For a while, I was actually able to get it back instantly and temporarily by eating chocolate, but for whatever reason that doesn’t seem to work anymore. Additionally, if I first lose my speech, then either meet someone I’m normally able to speak to or enter a safe space where I’m normally able to speak, I may not regain my speech even when I’m there. Sometimes I do, though, and lose my speech again as soon as I leave.

Since only my speech is impacted during selective mutism, along with writing or typing words I’m still able to emote and use body language, and nod/shake my head in response to yes/no questions. And because my vocal cords stop working during selective mutism, coughing, sneezing, yawning, laughing and even screaming are all completely silent, other than the movement of air in the case of coughing and sneezing. (My coughs, sneezes and yawns are generally always silent anyway.)

Some days I’ve contemplated whether my anxiety would be overridden by survival instincts and self-preservation when I’m feeling very ill or when I’m in danger, and I’d suddenly be able to vocalize my distress. All I can say is that so far, it hasn’t happened.

How I adjusted and made progress

In the first couple of years my mind and body were learning to work with this new condition I was afflicted with, I tried on numerous occasions to speak, only to feel tremendous pressure both externally (from others) and internally (due to my anxiety). The tight feeling in my chest became tighter, breathing became more difficult and my heart rate increased further. This became a constant occurrence in college, at church, and at pretty much any social gathering. Soon I realized no one in my circles then outside my relatives was going to hear my voice (except very specific individuals later on). Being relatively quiet anyway, I wouldn’t call this a painful realization, but quiet is relative; silence is, for the most part, absolute.

Here’s where things get interesting: as I got used to silence being my new normal over time, I learned to tell when I would be unable to speak in a given situation without having to try. (I never did find a way to ease myself into speaking no matter what I tried, and I had my smartphone to type on anyway.) Eventually this knowledge helped me identify new situations in which I wouldn’t be able to speak and saved me a lot of pressure by just not even trying something I knew right away was going to be futile, which continues to be useful today.

This is just about the only “choice” I make related to my selective mutism: I choose not to try speaking when I know it’s simply not going to work. But if I sense my ability to speak coming back to me, I’ll try. I absolutely will try. And in most cases, I do succeed.

There’s still pressure to respond to others in day-to-day conversation, of course, but at best it just ends up being a decision between pulling out my smartphone to type a response, not responding at all, or making like a tree and getting the hell out of there. For better or for worse, I’m probably still too sheltered by kind and understanding familiar faces to find myself in more than the rare situation of having to choose the last option.

By the grace of God (hey now, I did mention church just a few paragraphs up!), my condition has actually improved somewhat in recent years, even if not by a whole lot. I’ve found at least three safe spaces where I have anywhere from an 80% to a 100% chance of speaking, with only the most unexpected of circumstances catching me off-guard and disabling my speech. I may still be consistently unable to speak at church (for reasons I don’t wish to get into), and I may have a bad feeling about any on-premises job opportunities that may happen to come my way, but I’ve noticed that when I’m alone, not only can I talk to myself, but I’ve also begun speaking to service employees and passers-by on certain occasions.

The latter does still take tremendous amounts of courage, but the reason I try at all is because somehow I’ve been able to recognize opportunities to speak (remember, I don’t even try if I know it won’t work). I think I owe this big time to my journey in learning to be independent, both emotionally and in terms of taking care of myself. For someone on the autism spectrum with an anxiety disorder, this is a very big deal. It’s several slow, uphill battles in one.

Diagnosis

One thing I need to point out is that my selective mutism is self-diagnosed (and my therapist is aware of this). The main reason for this is that, according to the DSM-5, a person cannot carry simultaneous diagnoses of autism and SM. In reality this is because autistic people can experience non-verbal episodes as a result of meltdowns or other factors that aren’t directly related to anxiety — this is discussed further down — and unless the patient is able to determine and articulate the specific causes of their silence, it’s difficult for a professional to make the right call.

This does leave folks like me, who are acutely self-aware of and understand what causes their silence, in the dust. Self-diagnosis is not something that should be treated lightly (do your research, don’t latch on to a label the moment you encounter it, etc), but it can be valuable in situations where professional diagnosis simply isn’t an option. The goal, either way, is understanding and getting help, and that’s what’s most important.

For non-autistic (i.e. allistic) people, since selective mutism is still not very well understood, YMMV greatly when seeking a professional diagnosis. In fact, as we’re the ones with firsthand experience, I dare say we’re in a very good position to help our therapists identify our condition and in turn the right set of intervention strategies. This is probably true for many other mental health conditions and even some physiological conditions. Again, the ultimate goal is to learn what we can do to manage and hopefully improve our condition, and in turn our quality of life.

How you can help someone with selective mutism

So, you know someone who doesn’t speak at all, and if they do try, they struggle and probably never manage to do so. If you’ve not interacted before, they may get anxious when you initiate conversation. Many selectively mute people don’t manage to respond, even if we have AAC alternatives, to new people, and this is often out of fear that we may be judged for responding in a way other than speaking, which is, understandably, unexpected to most.

Remember that selective mutism has its roots in anxiety. So, as with other anxiety problems, your goal is to help the person feel comfortable. Specifically, comfortable in their silence, assured that you will not judge them for how they communicate (if they do so at all). It can take a while to get used to someone who doesn’t speak, but it’s important to respect their alternative means of communication. Remember that both of you share the exact same goal of communicating; only the method differs.

Here are a few key ways you can help a person with selective mutism be comfortable:

- Talk to them like you would anyone else. The only difference between a person with selective mutism and anyone else is that we can’t communicate verbally. Some people with selective mutism are able to communicate just fine using other methods such as writing, typing, or AAC. Others may not even be able to conjure the words to say. But what we all have in common is that, unless we identify as Deaf or hard-of-hearing, we can hear and understand spoken language the same way as others who can do the same.

We recognize that speaking is more efficient than writing or typing, which is why we’d happily speak up if only we could ourselves, so please feel free to keep talking and don’t feel like you need to switch to the same mode of communication as us if it means slowing yourself down in the process.

-

Allow them to respond on their own terms. When you initiate conversation, do be patient. Do not hurry them to respond, do not repeat your question unless their body language suggests they want you to do so (e.g. cocking their head with their ear toward you, which is what I do), and do not say things like “Hello?” or “Did you hear what I said?” or “Talk to me!” or, worst of all, “Are you deaf?” (often used for hyperbole or rhetoric but can be deeply offensive to anyone with speech and/or hearing disabilities, and IMO in its rhetorical form should be eliminated from any form of conversation as it’s incredibly rude anyway)

If it looks like they might have been distracted by something else and you’re unsure if they caught what you said, it may be appropriate to ask them if they heard you. But if it’s clear that they’re paying attention to you, e.g. by appearing focused on the conversation, waiting on you, facing you, or even making eye contact (which not everyone can do when anxious!), chances are they are paying attention and implying otherwise is going to come off as patronizing and dismissive of them. Use your best judgement here.

-

Avoid mentioning or otherwise bringing attention to their silence. The person is aware they can’t speak and any reminder thereof is only going to pressurize them further. Don’t ask them why they’re not talking either; they don’t owe you an explanation. Some of us will proactively explain to you in writing or text, but not all will.

Instead, treat the interaction as if their silence were inconsequential (because, if you think about it, it actually is). You want to remove the pressure of speaking, and for us this means staying as far away from “that” topic as possible. Focus on the actual topic at hand, and you’ll both be fine.

-

If they do start speaking, try not to act surprised, and avoid bringing attention to their speech. It might seem counter-intuitive not to congratulate or praise someone for making a breakthrough, but once again the key here is to keep the pressure low. Act like the person has always spoken. Continue the conversation as normal, and avoid verbally acknowledging their speech, at least until after you’ve finished this conversation.

Many of us understand how emotional it can be for someone else to hear us speaking for the first time after knowing us for months or even years. We’re just as, if not more, thrilled when we finally break our silence. You can be sure that our joy is shared. And in most cases it’s totally OK to acknowledge this after the fact, at a time we’re comfortable (again use your best judgement to determine this).

-

If a person with SM suddenly finds themself unable to communicate even with AAC, they may be very stressed, or there may be other factors affecting their ability to conjure a response. I often experience this when I’m in a group interaction or I have to make a time-sensitive or otherwise significant decision. Unfortunately, I don’t have much guidance for you here; the only thing that’s worked for me is quite honestly removing myself from the situation altogether. That’s not always an option though, so most decision-making situations end up in decision by inaction.

But yes, if possible, try to relieve the pressure on the person by telling them it’s OK not to answer. Suggest some options for them and see if they’re receptive to any of them. If all else fails and you absolutely can’t remove them from the situation, you may both have to ride it out like I’ve had to do. I know how it feels for someone else not to communicate to me, so I can understand your frustration. In fact, this may be the only time my friends still show signs of impatience, and I don’t blame them one bit. Caring for a person with anxiety or any other mental health issue is never easy for anyone involved.

Depending on the individual, you may never ever get to hear their voice. I’ve had friends who have been waiting for eight years to hear my voice, and still haven’t had the chance to. Although they sincerely hope for a chance to someday, they do not resent me or think any less of me in the meantime. I’m still a friend to them, and they’re still a friend to me. I just happen to be someone who communicates in a different way. If this describes your friendship with someone who doesn’t speak (for any reason at all, really), then you have my utmost respect and gratitude, even on their behalf.

Emergency Chat and other AAC apps

The reason I say I’ve been very fortunate is because ever since the day I first lost my ability to speak, I’ve been surrounded by very patient and understanding people in various areas of my life. I haven’t really met anyone who’s been dismissive or combative or mocking of my condition, and all I’ve had to do is type in the Notes app on my smartphone, have the other person read what I have to say, and they’ll respond verbally. Not all of us have the luxury of being surrounded by understanding people, or having an alternative means of communication on hand.

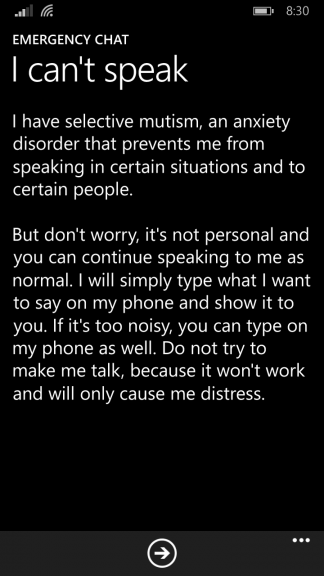

In 2014, Seph De Busser developed and published an Android app called Emergency Chat, originally designed for autistic people who become non-verbal as a result of meltdowns (which are distinct from panic attacks). It presents the reader with a splash screen with a heading and content that can be customized by the user for any situation that might render them unable to speak. This is followed by an offline, single-device chat client that can be used by one or both parties to communicate depending on the user’s listening needs.

Emergency Chat seemed like a great fit for selective mutism for this reason, which is why I contacted Seph, who then allowed me to develop Emergency Chat for Windows for my Nokia Lumia 830 with Windows Phone 8.1, as well as other Windows Phone users. Here’s a screenshot of my selective mutism splash screen at the time:

I depend on Emergency Chat pretty much all the time whenever I’m outside, save for the few safe spaces I mentioned above, and I’m just as thankful for the opportunity to use it each day as I am for the opportunities that I get to not use it. In a sense, you could say that Emergency Chat is my AT, though I’m not really sure to what sort of extent I’d call my own condition a disability — there are other conditions that impact my quality of life way more than not being able to speak on demand.

An iOS app is also available, but it hasn’t been updated at all since it was first released in 2015. It works, at least, but I can’t imagine the costs that go into keeping it on the App Store alone.

Other AAC apps exist that assist in various non-verbal situations, taking various forms such as PECS and text-to-speech, that may be helpful as well. I personally choose to have others read my words on screen, as text-to-speech often isn’t terribly efficient in my experience.

I can’t stress enough how important and helpful having an alternative means of communication at all is to most of us. It may present a slight inconvenience to you, but until the day comes that we overcome it, having something else that we can rely on to be heard matters.

Selective mutism and autism spectrum disorder

I was going to write about this myself, but I think Lilo, @A_Silent_Child on Twitter explains things perfectly. Here’s their thread about it — it’s a few tweets but not super wordy:

It's Selective Mutism awareness month… And I'm gonna have to ask y'all to not use "Selective Mutism" to describe your nonverbal periods UNLESS they are anxiety related.

I've seen it a few times before… And we can't do that. We can't steal a DX.

— Lilo the autistic queer (they/them) (@A_Silent_Child) October 4, 2018

Selective Mutism is a somewhat rare ANXIETY DISORDER

It is significantly less well known than ASD and people who have it suffer from the lack of knowledge professionals have about the disorder.

You don't help us when you call nonverbal periods Selective Mutism when they aren't.

— Lilo the autistic queer (they/them) (@A_Silent_Child) October 4, 2018

I have had people in the #actuallyautistic community argue with me that Selective Mutism is not always anxiety related.

That is wrong.

Selective Mutism is BY DEFINITION an anxiety disorder.

It is different from nonverbal or situationally nonverbal Autism.

— Lilo the autistic queer (they/them) (@A_Silent_Child) October 4, 2018

You can have more than one way of being situationally nonverbal.

Sometimes my nonverbal periods are caused by Selective Mutism.

Sometimes they are caused by sensory overload or processing issues related to Autism.

— Lilo the autistic queer (they/them) (@A_Silent_Child) October 4, 2018

If you have read about Selective Mutism and suspect you have it too, that is OK.

However, if you have not read about it and just saw the words and assumed it meant any kind of situationally nonverbal period, you are wrong.

And you're hurting our awareness efforts.

— Lilo the autistic queer (they/them) (@A_Silent_Child) October 4, 2018

I’ve lived with selective mutism for 9 years and 11 months, and autism all my life (did you think I was gonna say something clever there?), and in that time I’ve learned to skillfully tell what’s causing me to lose my ability to speak. In the overwhelming majority of cases, it’s anxiety. In fact, even before I developed SM, virtually none of my meltdowns rendered me non-verbal and the ones that did, didn’t for long. And it remains the case today (and I rarely ever have meltdowns anymore). Yeah, I find that hard to believe myself, but it’s true.

However — and this does bear repeating — selective mutism is an anxiety disorder and therefore should not be conflated with non-verbal episodes that have non-anxiety-related causes. This is more than just semantics; this can help you and/or your professional identify not just the right problem, but also the right set of solutions that will alleviate said problem.

Selective mutism and speech disorders

I do not have a speech disorder. However, I’ve gone so long without being able to speak to a large majority of people in my life (almost a decade), that my speech has noticeably deteriorated compared to before. Not clinically — I can still speak pretty coherently when I’m able to speak — but the difference compared to before this all started is definitely noticeable, at least to me anyway. This is why early intervention is important, folks.

Many people with speech disorders may choose not to speak as it can be exhausting to try and get the words out sometimes. This is fine, but it’s not selective mutism. They haven’t had their speech disabled by anxiety; they’ve simply chosen not to strain it. Some people who stutter or have other speech issues may get self-conscious and anxious about their speech — and if this anxiety directly disables their speech outright, then it’s possibly, arguably selective mutism, but even so it’s neither up to you nor me to judge.

A person’s struggles are their own; our role as listeners is to listen and understand what they have to say, again regardless of the method they use to communicate. And with that I shall segue to my final point…

Awareness, acceptance and advocacy

I don’t consider myself an advocate for selective mutism, at least not yet. Unfortunately I don’t really have the emotional maturity or physical resources (including time and energy) to handle that sort of thing. But I am proud to say that I was one of those interviewed during the development of Hush, a 2015 short film about selective mutism. Several more have popped up in the years since since, and I’ve watched a good number of them. I’ve also shared about my experiences with a few individuals on the Internet who contacted me, keen to find out more.

This 4528-word (excluding the table of contents) article is my first major foray into awareness and advocacy for SM, and while I don’t plan on making this a life goal or anything, I hope that this one-off contribution to this year’s Selective Mutism Awareness Month will help readers understand what it means to be trapped in silence in the presence of others, and help readers understand how to be a friend to me and those who suffer from the same condition. Because, trust me, I’m very fortunate to be surrounded by friends who are understanding. Not everyone shares my luxury. People get bullied and judged for not speaking up.

As a citizen of the Internet, I’ve been exposed to some of the most depraved human behavior you could ever imagine, and I share about my struggles fully aware that I’m opening myself up to reactions and responses of all kinds. But I also know that there are good people out there, who far outnumber the bad people, and just want to understand, empathize and help wherever they can. Understanding is a two-way street. Some people would do well to remember this.

Having said that, I’m happy to answer any questions you may have, as long as you ask honestly and in good faith.

2 comments

Hi,

I’m actually suffering from selective mutism from childhood and how I’m 19 and I’m still in it and none of family members have recognized it yet and I got to know at 18. My parents blame me for not speaking and beat me up and said me that they regret for giving birth to me so I have decided to leave them and live an independent life after 6 yrs as I have to complete my studies.

So is this decision of mine right??

I’ll be waiting for ur reply

Hi Deeksha,

I’m so sorry to hear about your situation. I’m afraid I’m not qualified to say whether you’re making the right decision. I’d really recommend seeing a professional about this. Thanks for reading and for writing in and I’m sorry I can’t be of more help.

Add a comment

Things to keep in mind:

* denotes a required field.

Please keep comments civil and on-topic.

Markdown is supported; examples include

**bold**for bold,*italics*for italics, and[hyperlinks](http://example.com)for hyperlinks. Learn more.You may choose to have your browser remember your name, email and website for the next time you comment. Your email address will not be shared either way. See the privacy policy.